A Game Money Can’t Buy - Malik Djoulait

Seen through an abstract lens, Malik Djoulait’s creative and narrative journey resembles a world map: a globe whose axis of rotation is basketball. Not simply as a sport, but as a cultural language, a social space, and a tool for connection. From his first blog in France to the iconic Quai 54, from a formative Olympic moment to the contemporary expression of African basketball, Malik’s path unfolds as a biography devoted to the Game, and to its universality.

Interview by Overseas | Gianmarco Pacione

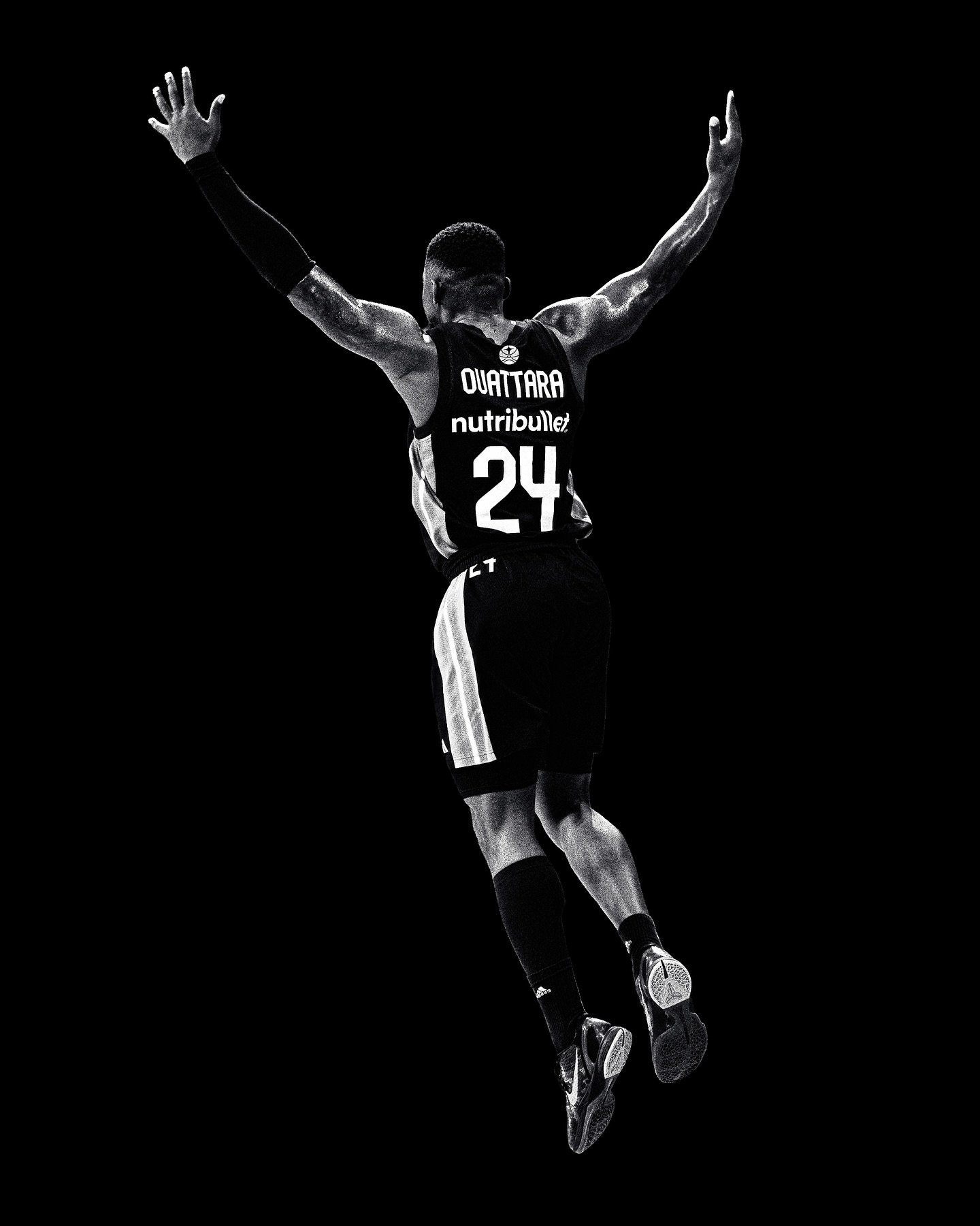

Photography Malik Djoulait

When ambition is driven not by financial desire but by purpose, something meaningful happens. Basketball teaches this. Art reinforces it. Malik Djoulait embodies it. Through storytelling, he has shaped a coming-of-age journey inspired by James Naismith’s original vision of the Game: one rooted in people, and culture.

Discovery and narration have gone hand in hand, shaping his personal and visual identity before his professional one. His work has traced the rhythms of French basketball in its formative years, captured the raw energy and cultural impact of Quai 54 at its modern peak, and then followed the Game across continents, in an on-going evolution. Today, that same sensitivity helps shape the aesthetic and narrative direction of African basketball, expressed at its highest level through the Basketball Africa League. Always with the same approach.

‘Dreams Money Can’t Buy,’ reads his Instagram bio. More than a motto, it is a mindset, and a precious statement. In this conversation, Malik Djoulait reflects on his creative journey and on a bond with basketball that is, above all, deeply personal.

[Overseas] How did basketball first enter your life, and when did storytelling become the language through which you chose to interpret it? In general, what drew you toward the intersection of sport, culture, and digital media?

[Malik Djoulait] I started with football before basketball slowly took over when I was around 12. With it came a whole cultural universe: hip-hop, streetwear, the NBA, and the lifestyle around the game. I played for nearly 20 years, but storytelling came early. At 14 (I’m now 35), I launched my first basketball blog when I realized the game was also about people, culture, and identity. Digital naturally became my way of sharing that passion.

[O] In your bio you write: “Dreams money can’t buy.” What kind of dreams are you referring to, and how have they evolved over time?

[MD] I’ve been on social media since I was 13, and that line has been my bio from the start. For me, it’s always been a reminder to stay grounded. My ambitions were never driven by money, but by purpose. Having the chance to tell meaningful stories, and to contribute to something bigger than myself is what truly matters to me.

[O] Turning to your photographic journey, could you tell us what initially inspired you to engage with this medium, which sources of inspiration have shaped, and continue to shape, your work, and what you ultimately seek in your documentary practice and visual compositions?

[MD] I’ve been working in content for about 15 years, but photography came into my life in a very simple and personal way. When the Olympics were announced in Paris, the city where I was born and raised, and I was lucky enough to attend the basketball games, I felt a strong need to preserve those moments. I wanted real memories, something I could one day share with my kids.

I borrowed a camera from a friend and started taking pictures with no real plan or expectations. I just wanted to capture what I was living in the moment. That experience stayed with me. Photography became a way to tell stories without words.

I was fortunate enough to take a photo that went viral, and that moment unexpectedly marked the beginning of my journey as a photographer.

[O] You oversaw the communication of a singular event within the basketball landscape, Quai54, for more than a decade. What was it like to find yourself at the very heart of what is, in every respect, a zenith of Parisian, French, European, and global basketball aesthetics and cultural vibrancy? And what kind of creative lens did you seek in the association with the Jumpman?

[MD] I was a fan first. Like many Parisian kids who loved basketball, I started going to Quai 54 in 2004 as a spectator, drawn by the game, the show, and what it represented for the city. I came back year after year, not only for the event itself, but because Quai 54 existed far beyond one weekend. You could feel its influence on playgrounds across Paris all year long.

Over time, through a shared passion, I got closer to the founders and producers of the event: Hammadoun Sidibé, Thibaut de Longeville, Said Elouardi, and Almamy Soumah. They trusted my vision, and what started organically evolved into a long-term collaboration. I’ve now been managing the content and communication for Quai 54 for more than a decade.

Being at the heart of Quai 54 means standing at the crossroads of basketball, culture, fashion, music, and identity. It’s more than a tournament; it’s a cultural statement. With Jumpman, the creative lens was always about authenticity and elevation, respecting street culture while giving it a global platform. The goal was never to over-produce or sanitize it, but to capture its raw energy, its codes, and its influence, and let Paris speak for itself through basketball.

[O] Your life has taken you through a wide range of experiences across different parts of the world. How has this sense of cosmopolitanism shaped you: both as a human being and as a communicator? How has it influenced your aesthetic vision? And how has your experience in university education contributed to shaping your perspectives as a contemporary storyteller?

[MD] It taught me curiosity and humility. There is no single truth or aesthetic. With Algerian roots, growing up in France, studying in the U.S., and traveling to more than 50 countries for both work and personal reasons, I learned the importance of listening and adapting. That sensitivity to context deeply shapes the way I approach storytelling today.

[O] Africa is plural, but it’s rarely told that way. How do you approach differences between countries, languages, visual cultures, and rhythms, when shaping content across the continent? Are there specific encounters or details that have reshaped the way you think about African basketball and its basketball society?

[MD] It starts with listening. Africa is not a single story, and basketball here carries history, ambition, and deep context. Our responsibility is to reflect that complexity honestly and humbly, while creating space for local voices within a global platform. That means never assuming. Each country, city, and club has its own rhythm and history. Some of the most valuable lessons come from local courts and communities, not from strategy documents. Every place deserves to be represented on its own terms.

[O] The digital ecosystem rewards speed, noise, and trends: how do you slow things down enough to protect meaning, depth, and intention? And what does basketball need to be/become, culturally, to remain relevant and compelling for new generations?

[MD] It’s about balance. Trends matter, but they are not everything. Not every moment needs to be amplified. Basketball and storytelling stay relevant when they remain human, intentional, and connected to real life.

[O] In Africa, basketball is rarely just about the Game. It’s about aspiration, belonging, and possibility. What kinds of human stories are you most drawn to right now, beyond highlights and performance? Are there any that feel particularly urgent to tell?

[MD] Stories of patience and resilience. Teams that struggled for years before winning. Clubs that kept trying before finally qualifying for the Basketball Africa League. Players who faced rejection before finding their place. These quieter journeys often carry the deepest meaning.

[O] You’ve witnessed the emergence of new leagues, new heroes, and new audiences. Do you feel a distinct African basketball identity is taking shape? If so, what defines it today, and where do you see it heading?

[MD] Yes, and it feels confident. You can see it when African teams compete internationally with their own style and presence. This year, seeing an African team finish third at the FIBA Intercontinental Cup was a strong and symbolic moment.

[O] Telling the stories of young athletes comes with weight: how do you think about responsibility, representation, and care when working with players who are still shaping who they are, on and off the court?

[MD] With care. These stories live far beyond a post or a highlight. Representation should protect dignity and growth, not rush exposure for short-term attention.

[O] Overseas often treats the Game as a mirror of society. Through your lens, what does basketball reveal about African youth culture today?

[MD] It reflects ambition, creativity, and global awareness. In many African countries, basketball is becoming part of everyday life, a shared language and a source of possibility. The goal is not for everyone to reach the biggest leagues, but to grow, set goals, and become a better version of themselves through the game.

[O] Looking forward. Which stories within African basketball still need time, patience, and trust to be told properly? And what excites you most about what’s coming next?

[MD] Long-form storytelling, documentaries, grassroots development, women’s pathways, and communities that are still underrepresented. What excites me most is seeing each country in Africa increasingly tell its own basketball story, in its own voice. There are so many powerful and beautiful stories still waiting to be told.